Endochondral Ossification

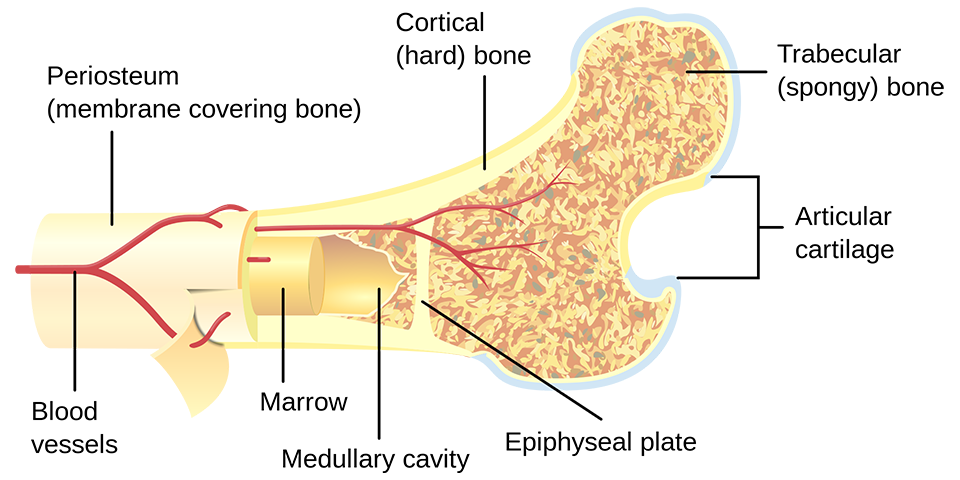

This process occurs in long bones and most other bones in the body; it involves the development of bone from cartilage. This process includes the development of a

cartilage model, its growth and development, development of the primary and secondary ossification centers, and the formation of articular cartilage and the

epiphyseal plates. Endochondral ossification begins with points in the cartilage called primary ossification centers. They mostly appear during fetal

development, though a few short bones begin their primary ossification after birth. They are responsible for the formation of the diaphyses of long bones, short bones and certain parts of

irregular bones. Secondary ossification occurs after birth, and forms the epiphyses of long bones and the extremities of irregular and flat bones. The diaphysis and

both epiphyses of a long bone are separated by a growing zone of cartilage (the epiphyseal plate). At skeletal maturity (18 to 25 years of age), all of the cartilage is

replaced by bone, fusing the diaphysis and both epiphyses together (a phenomenon called epiphyseal closure). In the upper limbs, only the diaphyses of the long bones and

scapula are ossified. The epiphyses, carpal bones, coracoid process, medial border of the scapula, and acromion are still cartilaginous.

The following steps are followed in the conversion of cartilage to bone:

- Zone of reserve cartilage. This region, farthest from the marrow cavity, consists of typical hyaline cartilage that as yet shows no sign of transforming into bone.

- Zone of cell proliferation. A little closer to the marrow cavity, chondrocytes multiply and arrange themselves into longitudinal columns of flattened lacunae. Zone of cell hypertrophy. Next, the chondrocytes cease

to divide and begin to hypertrophy (enlarge), much like they do in the primary ossification center of the fetus. The walls of the matrix between lacunae become very thin.

- Zone of calcification. Minerals are deposited in the matrix between the columns of lacunae and calcify the cartilage. These are not the permanent mineral deposits of bone, but only a temporary support for the cartilage that would otherwise

soon be weakened by the breakdown of the enlarged lacunae.

- Zone of bone deposition. Within each column, the walls between the lacunae break down and the chondrocytes die. This converts each column into a longitudinal channel, which is immediately invaded by blood vessels and marrow from the marrow cavity. Osteoblasts line up along the walls of these channels and begin depositing concentric lamellae of matrix, while

osteoclasts dissolve the temporarily calcified cartilage.